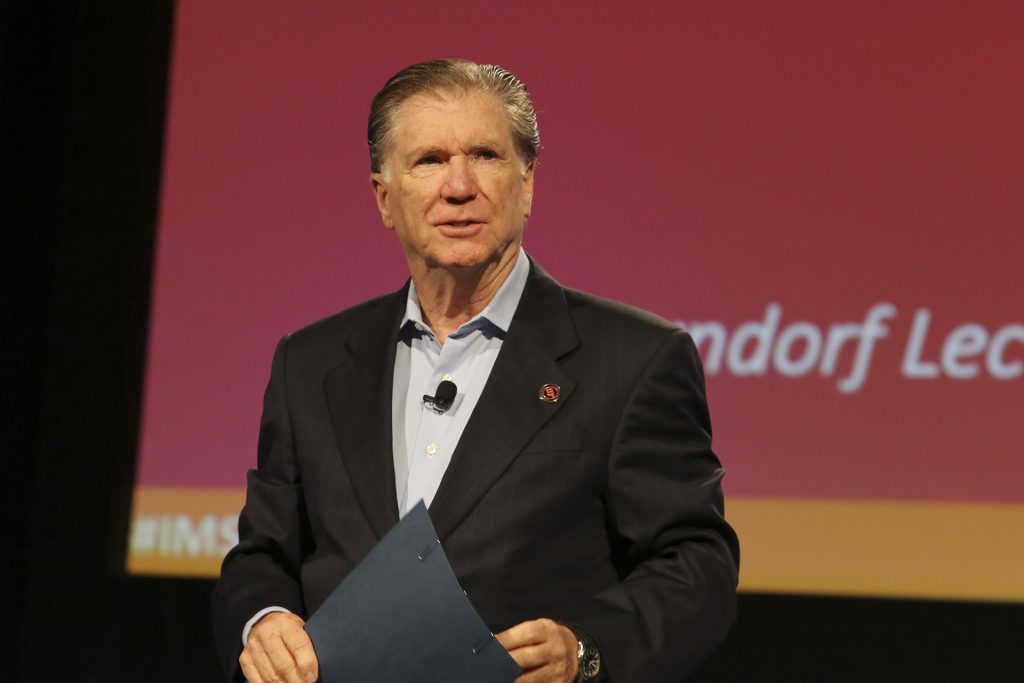

Explore the inspiring journey of Lou Oberndorf, a pioneer in medical simulation, from aerospace to healthcare innovation

Today we’re in conversation with Lou Oberndorf, a luminary in the medical simulation industry, whose revolutionary work has redefined healthcare education. In our exclusive interview, uncover the remarkable story of how Lou Oberndorf emerged from collegiate indecision to become a key architect in this cutting-edge field. We learnt about the audacity and vision that drove Lou to challenge the status quo, forever changing the landscape of medical training. And we dived into the wisdom of Lou Oberndorf, whose legacy continues to inspire innovation and excellence in healthcare simulation worldwide. Join us for a deep and inspiring dive into the life and triumphs of Lou Oberndorf.

Ciao Lou, thank you so much for agreeing to talk to our readers. And congrats on everything you are doing and what you achieved. This is the first time we are hosting an entrepreneur in our SIM Face series. We are very excited about this talk. So, let’s get started right away. How do you go from having a normal job, and one day you start a company, and that company becomes a really big company? Can you tell us about your story?

As an Air Force veteran with 11 years of service, including time in Germany, I transitioned into the aerospace industry, focusing on technology development and program management from 1977 to 1983. My career progressed well, and by 1994, as VP of Business Development at Loral Corporation, a leading aerospace and defense company, my role was to scout for emerging technologies and business opportunities for civilian applications, a challenging pivot from defense-focused operations.

During this period, I discovered an innovative medical simulation technology developed at the University of Florida by a team of anesthesiologists and engineers. It turns out, ironically, that one of the inventors was a past president of SESAM, Willem van Meurs, who was in the faculty at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida. Recognizing the potential, given the military’s long-standing use of simulation training, I saw an opportunity to introduce this to medical education—a field ripe for such innovation.

Initially, the aerospace sector struggled to integrate into commercial markets like healthcare. However, when the project faced potential termination, I saw the transformative potential in medical simulation. Proposing to purchase the license, I secured the deal and founded a company to commercialize the human patient simulator, initially called “Gainesville anesthesia simulator”, because it was originally designed for anesthesia training. Uhm, coincidentally, as the readers may know through the history, the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation funded two programs: one at the University of Florida, Department of Anesthesia, and the other one at Stanford University at the VA Center under Dr. David Gaba.

Despite competing against larger companies and overcoming skepticism in medical education, I secured corporate investment and additional funding. This entrepreneurial leap was driven by a personal desire for change after decades in corporate and military roles, culminating in the establishment of a venture that aimed to revolutionize learning in medicine.

I well believe that it was not an easy decision to move from aerospace to medical simulation. And could you now survive without your simulators?

It is an intriguing question. After selling my leading healthcare simulation company to CAE, I experienced a period of success and satisfaction. However, the elation of the sale was quickly followed by contemplation about my future. Despite the financial gains and happiness it brought to my family and employees, the next day I faced the inevitable question of what comes next. Bound by a non-compete agreement, I was temporarily sidelined from the simulation business. Yet, this didn’t prevent me from remaining an active community member. Years later, my passion undiminished, I returned to the simulation arena as chairman and CEO of Operative Experience. The field of simulation isn’t just my career, but a fundamental part of my life.

It’s clear that my dedication to this industry and community is lifelong; I cannot envision a future that doesn’t involve simulation in some capacity.

What has been your most satisfying moment in your career?

Boy, that’s a tough one. I know.

Reflecting on my journey as an entrepreneur, I can’t pinpoint a single defining moment; it’s been a mix of challenges and victories. Navigating a small business meant facing tough financial hurdles, from funding to payroll. The turning point came when we strategically expanded our market from medical to nursing education, despite initial resistance from the medical establishment. This move was crucial, as nursing education has become a vital component of healthcare worldwide.

Another proud achievement was the establishment of professional societies, signaling the acceptance and need for a communal framework around our simulation technology. Furthermore, adopting an international focus was a deliberate choice from the beginning. Remarkably, two of the first three human patient simulators we sold at METI were to international clients—in Bristol, UK, and Wellington, New Zealand—setting us on a path to becoming a globally recognized company. These moments, collectively rather than individually, highlight the pivotal steps on my path to success.

It’s a matter of fact that you are a pioneer as an entrepreneur in simulation. What good, difficult, new, unexpected things has a career as an entrepreneur in simulation brought you in your life story so far?

In recounting my 25-year journey, a source of deep satisfaction has been connecting with exceptional individuals in healthcare—some of the most intelligent and dedicated professionals one could meet. Their commitment mirrors what I admired in the military: dedication and teamwork. These encounters have not only enriched my life but also brought my family, including my wife Rosemary, into a world that has acknowledged our contributions.

My career has revolved around three passions: technology, education, and embracing risk as an entrepreneur. Early adopters of our simulation technology risked their careers, and seeing this support was humbling. This path has profoundly impacted my family, guiding our involvement in education, from scholarships to supporting healthcare education at various levels. This commitment to education and healthcare has been a rewarding aspect of both my professional and personal life.

We recently published an autobiography of a sim inventor who also worked in your company, he worked for you. You’ve mentioned him earlier, Willem van Meurs. So, in general how did you select your staff?

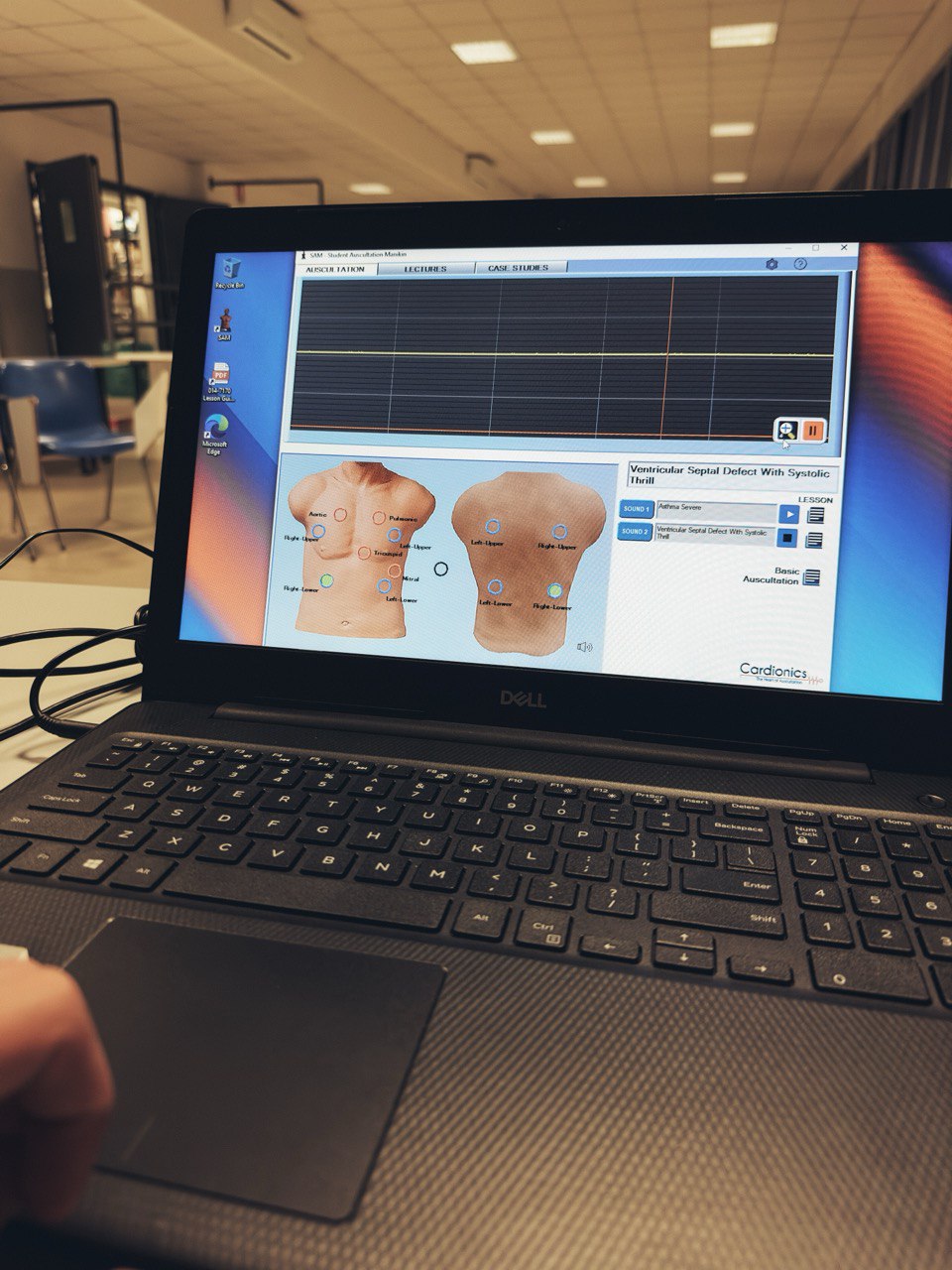

Starting my company with five staff members, including two engineers already familiar with our simulation technology, was key. We also had an executive managing the program. A significant breakthrough was the automation of human physiology in our simulations, a feature still critical today. This leap forward was largely thanks to the work done in Gainesville, with notable contributions from David Gaba at Stanford.

We lacked expertise in physiology, which is where Willem van Meurs came in, consulting us with his in-depth knowledge. We eventually hired two of his graduate students, Hugo Azevedo and Marco Grit, who left academia and made significant strides in the industry. These hires under the ‘van Meurs Physiology tree’ were pivotal, bringing fresh talent into our fold.

Key figures in my professional journey include Dr. Michael Good, an anesthesiologist part of the original invention team, who later became the dean of a medical school. He was a mentor to me, particularly in medical education, helping bridge the gap in our understanding of simulation’s role in this field.

At METI, our drive for education guided us to learn medicine and harness simulation technology, key to designing innovative simulators. We recruited experts in technology and engineering, and sales staff with healthcare backgrounds like nursing, who transitioned from clinical roles. As we expanded, we brought on professionals in HR, manufacturing, and production, while specialized hires focused on healthcare modeling, simulation, and medical education.

You know the world of simulation very well, in a few words what are the unmet needs today? What are the current trends that are driving the healthcare simulation industry?

The constant need in our industry is to embrace risk and innovation, particularly in teaching and communication through technology. For a decade, I’ve championed maintaining our foundational entrepreneurial spirit. Everyone in our community is essentially entrepreneurial, always seeking novel teaching methods and ways to connect, with a significant focus on adopting transformative learning technologies. Virtual reality (VR) has long been promised, while artificial intelligence (AI) is a more recent, frequently discussed topic. Despite my traditional leanings, I believe we can’t fully replace physical simulators; hands-on experience remains crucial in healthcare training, despite some technologists’ disagreement.

VR has been around, used by the military long before it entered our domain, and it holds potential, though it still struggles with scalability and affordability. Augmented reality (AR) seems more immediately applicable, enhancing physical simulators. While AI is an exciting and somewhat intimidating prospect, I anticipate it will advance more rapidly than VR because it isn’t as dependent on physical hardware. These simulation technologies—VR and AI—present the significant challenges and opportunities ahead for us.

You said throughout your career you have met many people and worked with many different simulationists. Was there someone who had a lasting impact on your work, and what was special about this person?

In my mental rolodex, two names stand out. Frank Lanza, from Loral and later L-3 Communications, served as my corporate mentor with enduring influence on my leadership and business approach. Dr. Mike Good, an attending anesthesiologist and one of the inventors who facilitated our entry into medical simulation, lent credibility to our work at METI and has since had a distinguished career in medical education and healthcare delivery, now leading Utah Health.

Tore Laerdal is another significant figure. A competitor and visionary leader of his eponymous company, he provided me with daily motivation and earned my profound respect, despite our fierce competition. These individuals, along with inspirational nurse educators, deans, and military simulation experts, shaped my career, but it’s Good and Laerdal who are paramount in my story.

You had a brilliant career, and now you seem to want to give back to society. Some examples: The Rosemary and Lou Oberndorf ’63 Endowment fund at the Seattle Prep, Rosemary and Lou Oberndorf Fund at Sarasota Art Museum, Lou Oberndorf Lecture at SESAM and IMSH, the Lou Oberndorf Professorship in Healthcare Technology at the Florida University, the recent Oberndorf College of Medicine AI Prize at the College of Medicine, is there any specific reason??

My parents instilled in me the value of caring for others rather than mere charity. As a first-generation college graduate in the U.S., with neither of my parents having had university education, the importance of education has been central in my life and my wife’s, who is also a first-gen graduate. Opportunities for education I received, often through philanthropy, have shaped my family’s philosophy. We’re committed to the advancement of knowledge and providing educational opportunities wherever possible. Our success in the simulation community obliges us to give back, and through roles like delivering keynotes, we stay involved and contribute to the industry. It’s a natural extension of METI’s ethos and reflects our personal commitment to educational access and advancement.

I love this sense of giving back, really. What advice would you give to a new simulation entrepreneur who wants to play a role in shaping the future of simulation?

Launching a successful business isn’t easy amidst a sea of ideas, many of which only offer incremental improvements. It’s crucial to differentiate between a genuinely innovative concept and a minor upgrade. A sustainable business can’t be built on incremental changes alone. Entrepreneurs must be self-critical and ready to prove their concept’s worth, starting with adoption by their immediate peers, particularly in academia. If your own colleagues aren’t using your technology, it’s unlikely to persuade others.

In addition to convincing your colleagues, funding is a significant hurdle. Entrepreneurs often underestimate the required capital and time. Conventional wisdom advises having at least six months of operating expenses saved up, but even that may not suffice. Lastly, scalability is vital; without it, even the most innovative technology won’t evolve into a successful enterprise. These are the tough lessons I emphasize to aspiring entrepreneurs.

What are your future plans? I know it’s going to be complicated because there are many, but try to make a summary of your future plan.

I’m committed to growing my current venture, Operative Experience, by seeking partnerships to ensure our stability and growth. Personally, my family and I remain dedicated to education and philanthropy, continually seeking to ‘pay it forward’. We are always on the lookout for new opportunities to expand our educational efforts, a commitment that’s integral to both our present actions and future plans

And here is our SIMZINE question. If you had the chance to start your career over again, what would you do differently?

I don’t know that I would have done anything different. I can look back. I think we’ve been blessed that we have at least something positive and success that we can look at and channel. Considering my journey, I might have chosen law school at one point, unsure of my direction after college. Yet, life’s serendipitous turns led me to simulation, a field I would come to thrive in.

Though ignorance of the enormity of changing medical education might have been bliss, it was the catalyst for my venture. With hindsight, I recognize the importance of ample resources and realistic expectations for startups—lessons that came through facing and overcoming challenges.

Despite any potential for more humility or confidence, I wouldn’t alter my path. It’s been a blessed and recognized one, and any arrogance I had was just a veil for the confidence needed to push through. This conversation has mirrored my career: a transparent reflection on a well-trodden path, leaving me with no desire for change.

Thank you for this candid reflection on your journey. It’s inspiring to hear you express no regrets and maintain a stance of gratitude for your successful and recognized career. Your insights today have been incredibly valuable, and I appreciate your openness in sharing them.

READ ALSO